Associate Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Combining forces in one machine

A hard-turning/grinding combination machine drastically reduces processing time

- By Lindsay Luminoso

- December 21, 2020

- Article

- Metalworking

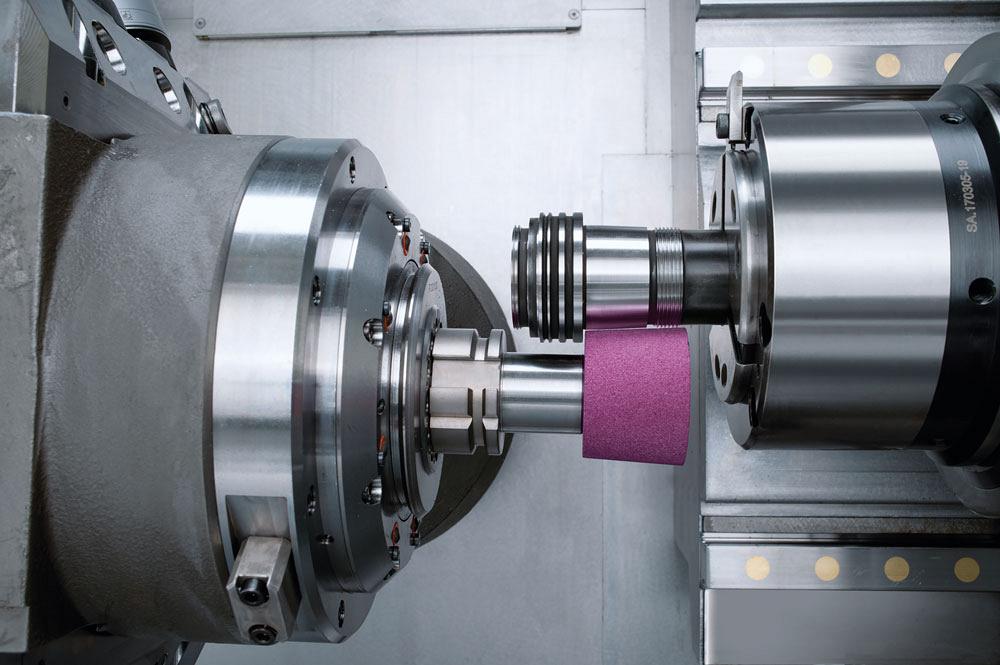

Prehardened materials can be problematic to machine. But with a combination machine, a shop can use hard turning to remove small amounts of material first. The advantage is that it allows for better control of the remaining grinding allowance. Image courtesy of Index.

Combination machines are becoming more commonplace on the shop floor. The more operations that can be processed on one piece of equipment, the better. Not only does this development limit the amount of floor space needed, it can also speed up and increase accuracy of part processing. Typically, the capital outlay needed for grinding applications can be very high. But when you combine both grinding and hard-turning applications on one machine, you can reduce capital equipment costs as well as operational costs. This is part of the reason that combination hard-turning/grinding machines are becoming so popular, as these two complementary processes just make sense combined in a singular unit.

"Manufacturers are increasingly looking to eliminate as many operations as possible," said Randy Carlisle, applications engineer, Index Corp., Noblesville, Ind. "Prehardened materials or those in the 58- to 62-HRC range can be problematic to machine from the start. A manufacturer can use hard turning to remove small amounts of material at a time. The advantage of this is that it allows for better control of the remaining grinding allowance."

For the most part, grinding is used to achieve surface finish and possibly roundness requirements. If a part can be hard-turned first, an operator can control how much material is available for the grinding wheel, adjusting as needed to reduce wear and limit downtime. It is a much more efficient use of a grinding wheel to remove only 0.002 in. rather than having to take off 0.01 in., which can be done using hard turning. It also extends the life of perishable tooling, whether cutting tools or grinding wheels.

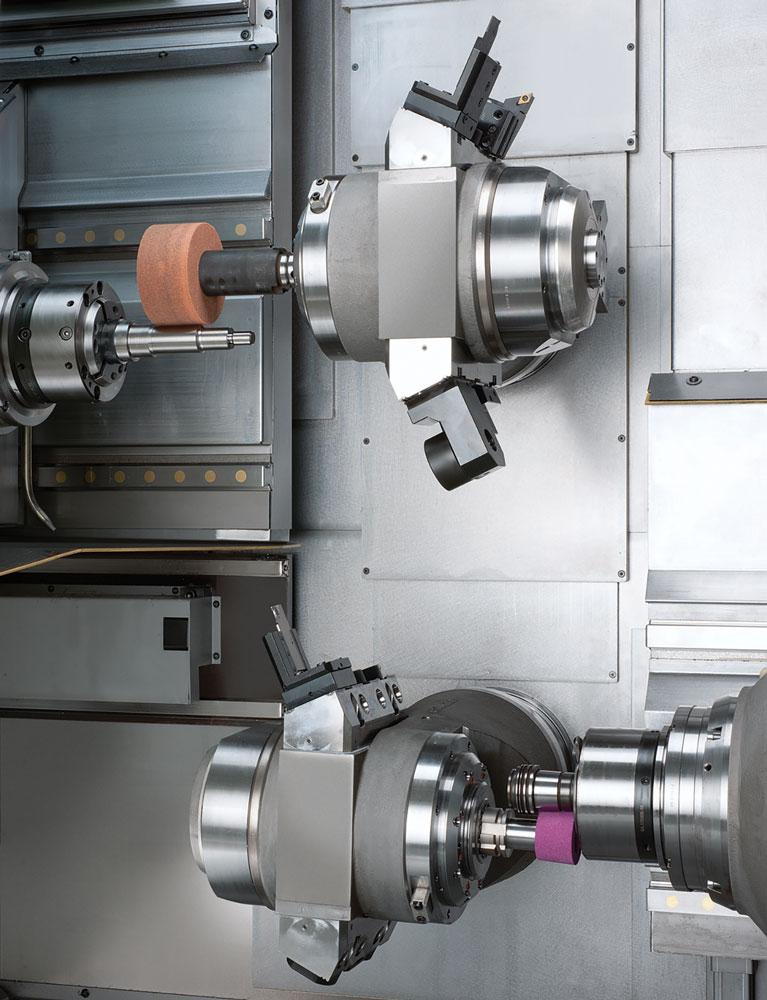

"Another benefit comes with datum control," said Jeff Moore, regional sales manager, EMAG, Ont. "Tolerances are becoming tighter and tighter, with materials becoming more challenging to machine. It doesn’t make sense for a shop to take a part once it has been hard-turned, remove it from the clamp, move it to another machine, and reclamp it on a grinding machine. It’s challenging to re-establish the datums from the turning to the grinding."

Having a part on a singular machine that needs to be clamped only once makes a big difference when it comes to meeting the tight tolerances. On two separate machines, an operator must maintain much tighter tolerances at the hard-turning stage than on a combination machine that doesn’t require reclamping. Not to mention, it can save time. Clamping a part just once, a shop can improve the quality and capability of the process.

Once all the grooves and heights are hard-turned into a component, the machine can seamlessly switch to a grinding operation to finish off the surface.

"Even if a surface needs to be ground, we always recommend that it’s hard-turned first," said Moore. "This can help reduce cycle time by quite a bit. Also, by turning first, shops can produce more consistent parts, as the amount of material needed to be removed through grinding is always the same. This will also improve grinding wheel life."

For all its advantages, sometimes a combination machine isn’t suitable. For shops that work with softer materials, anything around 22 HRC, it just makes sense to stick with turning. In fact, grinding softer materials can cause buildup or damage the grinding wheel itself.

On the other side of that, if a shop works with parts that have many tapered surfaces or multiple faces requiring grinding, say upwards of 90 per cent, then the experts recommend going with a stand-alone grinding machine.

Whether a combination machine really can improve throughput depends on the application, part runs, and quality requirements that a shop takes on. However, the fewer times an operator needs to handle the part, the better. With a combination machine, the operator needs to clamp the part only once and the machine does the rest.

Putting a part on a single machine that requires only one clamping makes a big difference when it comes to achieving tight tolerances. Image courtesy of Index.

Which Applications Make Sense?

There are a number of industries for which a combination machine is particularly suited. The experts point to automotive and oil and gas components as an area of opportunity for using combination machines.

"The application where I see combination machines working is with automotive transmission components," said Moore. "A lot of transmission components, clutch components, gears, and pinion shafts are all made from heat-treated materials. Post hardening, a shop can hard-turn the surfaces to maintain a datum structure on the input and output shafts."

Moore added that he sees the electrification of vehicles to be a great opportunity for combination machines, particularly with the production of rotor shafts.

Many of today’s big automotive firms are producing vehicles that have tighter tolerance restrictions than ever before. Not all surfaces can be solely hard-turned, and in many cases, companies like General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, and Honda specify on the drawings which surfaces require grinding, the surface finish requirements, and the surface lay direction needed for the operation it is intended for.

"We see that many companies producing a large number of automotive components can benefit from a combination system," said Carlisle. "But we also see this being useful to the petroleum industry and oilfield technology. It’s important to look at quantity, though. These machines are expensive, and a shop should look at the quantity and part runs that are expected and whether a new machine is justified. If a job shop is actually quoting upwards of 300 part runs, depending on part characteristics, it might not justify this type of technology. However, many of today’s machine shops are moving beyond the traditional work flow of moving parts from machine to machine throughout the shop and really looking to combining operations when warranted."

What to Look for in a Combination Machine

Design and reliability of a combination machine will play into how successful a shop can be with this technology. Because applications for combination machines generally tend to need to hold tight tolerances, even in parts that require just hard turning, rigidity and accuracy are essential.

"As far as grinding is concerned, grinding machines are built for grinding, and most turning machines are not," said Carlisle. "This makes the design of the combination equipment so important, and it’s really important to focus on features. One of the big things to watch out for is how coolant is handled and removed from the machine."

Moore also noted that the construction of the machine is a significant factor in how effective the combination machine will be.

"All EMAG turning machines are capable of grinding because they are constructed using polymer granite MINERALIT bases," said Moore. "We can maintain thermal stability by heating or chilling the machine to shop ambient temperature, along with the glass scales on the axis to hold tight tolerances repeatedly. Another important feature is the ability to ID and OD grind and hard-turn with a single clamping. Some machines also have the ability to grind tapers using a B Axis on the ID spindle, which will expand the types of parts shops can take on."

Where the Technology Is Headed

Hard-turning/grinding combination machines are not new, but more shops are willing to explore these hybrid process options than ever before. These machines, much like their stand-alone counterparts, are become smarter and more sophisticated.

"The technology we see in the market today, that exists out in the rest of the machine tool world, was on the drawing board just a few short years ago," said Carlisle. "Smart technology is being adapted to make combination machines more intelligent than ever before. We are seeing boring bars with sensors and technology that is able to communicate with the controls. As far as grinding goes, we are using ring sensors that, in creep mode, can detect how close or when the grinding wheel comes in contact with the part and when to start the grinding cycle. It can also keep control over what the size of the wheel is and the necessary offsets."

In addition to smart technology, many combination machines are going beyond the traditional hard-turn/grinding operation and incorporating skiving as well.

"Skiving is a next opportunity for a lot of shops to start saving some money in that case," said Moore. "We see a lot of shops producing rotor shafts where the sealing surfaces are done by skiving and the bearing surfaces are done with grinding. In many cases, a part can’t have any patterns left over from the turning operation. So, with a twist-free or scroll-free turning, you get that functional surface. Skiving is faster than grinding and hard turning, meaning cutting times and tooling costs are reduced."

Associate Editor Lindsay Luminoso can be reached at lluminoso@canadianmetalworking.com.

EMAG, www.emag.com

Index Traub, us.index-traub.com

About the Author

Lindsay Luminoso

1154 Warden Avenue

Toronto, M1R 0A1 Canada

Lindsay Luminoso, associate editor, contributes to both Canadian Metalworking and Canadian Fabricating & Welding. She worked as an associate editor/web editor, at Canadian Metalworking from 2014-2016 and was most recently an associate editor at Design Engineering.

Luminoso has a bachelor of arts from Carleton University, a bachelor of education from Ottawa University, and a graduate certificate in book, magazine, and digital publishing from Centennial College.

Related Companies

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

Automating additive manufacturing

Sustainability Analyzer Tool helps users measure and reduce carbon footprint

CTMA launches another round of Career-Ready program

Sandvik Coromant hosts workforce development event empowering young women in manufacturing

GF Machining Solutions names managing director and head of market region North and Central Americas

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI