Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Keeping the fire of innovation alive at SBI

Fireplace manufacturer stays competitive with automation investments that get the best out of new tech and keep employees engaged

- By Rob Colman

- August 11, 2022

- Article

- Fabricating

SBI is a family-owned business that designs, builds, and markets residential heating products—primarily solid fuel stoves and fireplaces. SBI

The challenge with introducing any automation in your production is making sure it improves the working life of existing team members rather than complicating it. St-Augustin-de-Desmaures, Que.-based Stove Builder International (SBI) is an example of a company that is continually finding new ways to adopt new technologies while keeping its team engaged. Its newest investment, a TRUMPF TruLaser Center 7030, is just the newest of many such investments.

SBI, as its name suggests, is a family-owned business that designs, builds, and markets residential heating products that are sold internationally, although the majority of its business is in Canada and the U.S. The company really came into its own in this sector when it purchased the Drolet brand in 1999—a brand that has a history in the province since the late 19th century. Since then, it has grown through 10 more product acquisitions and organic expansion, making primarily solid fuel stoves and fireplaces. It currently employees 260 people and builds 50,000 stoves and fireplaces a year.

Competitive Vision

Staying competitive in the market has required investing in automation wherever possible as the technology has matured.

“Our vision has always been the same: We want to grow by being super-efficient,” said Jean-François Cantin, vice-president of SBI. “I always tell people in the shop, we have to make sure we make more with the same people, and we want to make sure those same people enjoy their jobs more all the time. The goal is to put the tools in the shop that allow us to double or triple production without making life more difficult for our team. We want it to be a place where you can learn how to use technology that maybe you are one of just a few using it in Canada. That’s what we try to do.”

SBI works at being a “fast follower”—adopting technologies once they’ve been proved out by a few leading companies.

“As a company making fireplaces, we can’t afford to be a beta adopter of technology—we have to know it’s going to work right away.” One of the first areas where the company introduced robotics, for instance, was in its paint booth, introducing an ABB robot. “Using a conveyor, we can determine where a product is and how it’s positioned in space, and the robot can paint it,” said Cantin. “But prior to that we had one team member who made sure tough-to-reach areas of any product are painted. Much of our automation is this kind of combination of automation and human operators.”

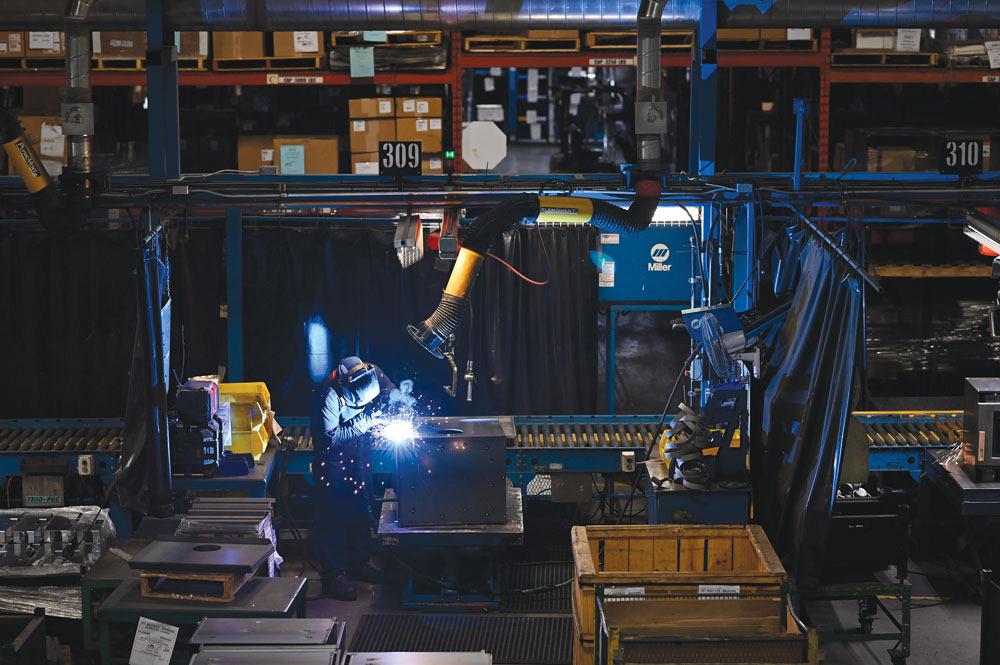

The company’s welding area is similarly divided.

“There are some very long welds on our products that are done over and over, and that’s where robotic welding really shines—the robot doesn’t get fatigued, it’s steady, and does the same job all day,” said Cantin. “But in between robotic welds there is positioning and tack welding that need to be done unless we want to create very complicated jigs. For this reason, our weld operations go from robot to person to robot to person to robot again.”

Even this arrangement has become more sophisticated over the years.

“We used to have only one robot at the beginning of our welding processes because any distortion on the product after a few weld processes made it difficult for a robot later in the process to follow a seam,” Cantin explained. “Now with vision systems and seam tracking, this is no longer an issue.”

“There are some very long welds on our products that are done over and over, and that’s where robotic welding really shines—the robot doesn’t get fatigued, it’s steady, and does the same job all day,” said Jean-François Cantin, vice-president of SBI. SBI

Team Engagement

Staff involvement is an important part of adopting these new technologies, said Cantin.

“No one is ever going to be in the lunchroom wondering about any new equipment being installed on the floor. In fact, if we are developing a three-year plan for a certain area of the shop, sometimes we will have an activity where we break the staff into teams and have them compete to design a layout for the technology that makes the most sense. Each group will present their ideas and defend their position. Ultimately management has to go away and make the final decision, but the involvement helps clarify the vision. The team is part of the process, and when they’ve been through that discussion, they understand what’s coming.”

Part Sorting Bottleneck

The variety of parts that SBI produces for its various products means that it has been valuable to have both punch presses and lasers in its production mix. Prior to the TruLaserCenter 7030 addition, SBI was operating two punch presses, two CO2 lasers, and one fibre laser. All of these are currently connected to a STOPA storage system to manage the flow of sheet metal to the machines and the flow of finished parts into storage. The modular storage system was modified to connect the new TruLaser Center 7030. This allowed SBI to add the newest laser technology offered by TRUMPF to the STOPA storage system already in place. The cutting department always runs 24-7, with a crew of three monitoring it at night.

“The two punching machines work very efficiently for us because they are attached to a system that removes the skeleton and stacks parts neatly in pallets to go back into the storage system,” said Cantin. “But the lasers did not have any part picking ability, so although we could run the machines lights-out, eventually we would have to remove parts attached with microjoints on the skeletons.”

SBI had between six and eight team members working full time just removing parts from skeletons and sorting them for presentation to its press brake department.

“It comes back to job satisfaction,” said Cantin. “Is it a great job to do? I don’t think so. And it is also a health and safety concern.”

The other issue for SBI is that it already had a TRUMPF BendMaster automated bending cell, used to bend large parts, normally a two-man operation when done manually. (The person monitoring this machine also bends parts on a small electric brake set next to the cell—a multi-tasking strategy that is becoming more common.) However, while it is very efficient at producing bent parts, it would be better served if cleanly cut material was sent directly to it rather than being held up in storage.

Beyond the limitations of its current machines, production needs were increasing. The question is, do you simply add another fibre laser or invest in newer tech? For Cantin, it wasn’t a difficult decision.

Integrated Cutting and Sorting

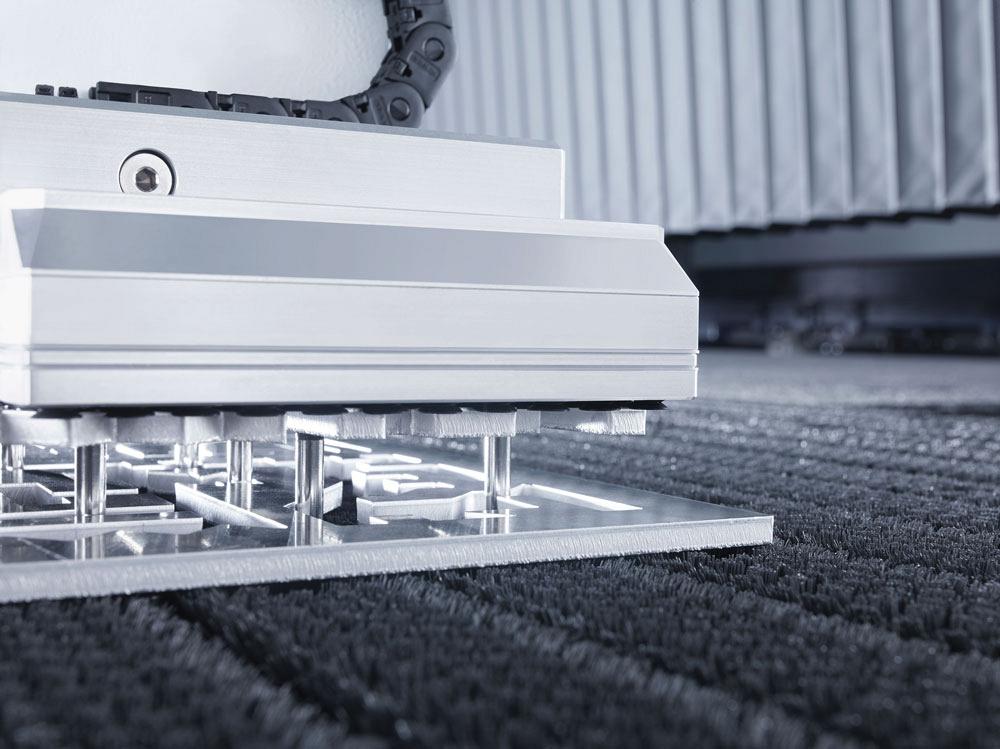

SBI chose to invest in TRUMPF’s TruLaser Center 7030, which operates more like a punching machine in the way that it sorts parts as it cuts, uses a brush table rather than slats, and moves both the sheet and the laser head. The machine was installed and running as of December 2021.

“TRUMPF came out with this system a few years ago,” said Cantin. “It has proved itself in the market enough for me to have confidence in investing in it. Now we can have complete automated flow from conception to the automated bent part.”

“But in between robotic welds there is positioning and tack welding that need to be done unless we want to create very complicated jigs,” said Cantin. “For this reason, our weld operations go from robot to person to robot to person to robot again.” SBI

The idea behind the Center is to more fully integrate cutting and sorting.

The full service laser machine’s design means that sorting works somewhat differently than what might be considered a “standard” part picking setup on a 2D laser cutting machine. For instance, smaller parts and scrap can be pushed through the support table’s SmartGate and into bins, meaning that the speed of the sorting isn’t slowed down by lifting smaller parts off the table (although a shop can choose to do so if they wish those parts to be placed with others in a kit).

In terms of cutting, the sheet is held by a clamp rail, so this is taken into account during the nesting process. And although common cutlines can be used, attention has to be paid to ensure that sheet integrity remains as parts are removed.

“It changes a bit how you nest,” said Cantin. “The software, of course, takes care of a lot of it. When you first look at it, you think you’re losing material. But I think you need to think about it globally. You might not be able to make parts as tight on a nest as before, but they come out perfect every time and stack easily. At the end of the day you might have a little more scrap, but it’s more than compensated by having good parts all the time.”

Sorting of parts is different as well. Small metal pins rise from the brush table to push a part onto a passive suction cup plate.

“If a part is bad quality, it will stop,” said Cantin. “Today even though you have an excellent laser, you sometimes get a part that is OK but not the quality it is meant to be, for whatever reason. In a normal setup, you’re going to stack the part and you’re not going to know later that you need to use something to cut it out of the skeleton, but by then it’s too late. You might have 200 parts that are cut incorrectly. With the Laser Center, if the problem happens, the machine has technology to alert you. Not only does it monitor the cut in real time, but pressure on the suction cups that lift the part can alert the machine to the problem. Am I grabbing that part and can I go away with it? If not, I need to do something. The machine can clean the nozzle to determine if that is the problem. But if it can’t pick or stack a part properly, it will stop, and you’ll know why and can solve the issue.”

And any errors on SBI’s machine don’t survive in a vacuum. All of these model machines producing in the market get fed back to TRUMPF in an anonymous form. If a machine in the field is unable to remove a particular geometry, the company takes that feedback and then trains its data models to recognize the geometries, re-optimize them, and send out an updated patch to the machines in real time so that they are continuously learning and feeding customer machines using artificial intelligence.

Quality Team, Quality Product

Since adopting the Laser Center late last year, production volume is such that all other cutting tech, aside from one of the company’s old CO2 lasers, is still being used. The only difference is that no parts are being outsourced anymore.

“The efficiencies of the Laser Center are being felt in the management of pallets,” said Cantin. “Where one person might take five hours to sort parts in a full pallet from our other lasers, the same job with parts from the Center might take 45 minutes, and this is primarily ensuring everything is properly labelled for sending on to our bending department.”

The Laser Center, like any with part sorting capability, is ideally suited to kitting assemblies. SBI uses this term but it’s more akin to organizing production batches of as few as 25 parts at once.

To improve its cutting and sorting speeds, SBI chose to invest in TRUMPF’s TruLaser Center 7030, which operates more like a punching machine in the way that it sorts parts as it cuts, uses a brush table rather than slats, and moves both the sheet and the laser head. SBI

“Because we are making our own product, we can take a strategic approach to optimization,” he said.

At this point, Cantin is certain that the company will invest in another Laser Center soon. It has proved its value. At that point, it may be time to consider more investment in the press brake department.

“The bend cell currently works alongside six other press brakes, and we currently don’t bend on every shift,” he said.

The Laser Center also is likely to continue to change the role of the laser machine operator.

“We currently have one person there to monitor and maintain all of our lasers, and one person for our punch presses,” said Cantin. “But when the machines are running smoothly, they have time to work on prototype parts and think of next steps in production ideas.”

It’s this sort of engagement that Cantin says is at the heart of adopting new technology.

“The quality of the team you have around your equipment is very important,” he said. “The more technologically advanced equipment you put in your shop, the more care you need to invest in it. If you don’t have a good maintenance team or good programmers who want to be involved in the process, if they don’t walk together into this and you put a machine like this on the shop floor, it’s not going to do well.

“Our team, since we installed this machine, it’s been like Christmas for them,” he continued. “The programmer talked to his wife and arranged to come in on the weekend to work with the operator to make sure they were happy with it. I didn’t ask for that commitment, but they wanted to see it working the best it could. You need that kind of passion.”

Passion has taken SBI on a road to further expansion. Just recently it announced the introduction of its first production centre in Virginia. Expect to hear more from this dynamic company again soon.

Editor Robert Colman can be reached at rcolman@canadianfabweld.com.

For sorting parts, small metal pins rise from the brush table to push a part onto a passive suction cup plate. “If a part is bad quality, it will stop,” said Cantin. “Today even though you have an excellent laser, you sometimes get a part that is OK but not the quality it is meant to be, for whatever reason. With the laser center, if the problem happens, the machine has technology to alert you. Not only does it monitor the cut in real time, but pressure on the suction cups that lift the part can alert the machine to the problem.” TRUMPF

SBI International, www.sbi-international.com

TRUMPF Inc., www.trumpf.com

About the Author

Rob Colman

1154 Warden Avenue

Toronto, M1R 0A1 Canada

905-235-0471

Robert Colman has worked as a writer and editor for more than 25 years, covering the needs of a variety of trades. He has been dedicated to the metalworking industry for the past 13 years, serving as editor for Metalworking Production & Purchasing (MP&P) and, since January 2016, the editor of Canadian Fabricating & Welding. He graduated with a B.A. degree from McGill University and a Master’s degree from UBC.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Industry Events

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI

17th annual Joint Open House

- May 8 - 9, 2024

- Oakville and Mississauga, ON Canada

MME Saskatoon

- May 28, 2024

- Saskatoon, SK Canada

CME's Health & Safety Symposium for Manufacturers

- May 29, 2024

- Mississauga, ON Canada