Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Ensuring cobot rollout success

A quick ROI on your first project could be key to the sustained success of the tech in your shop

- By Rob Colman

- January 11, 2021

- Article

- Automation and Software

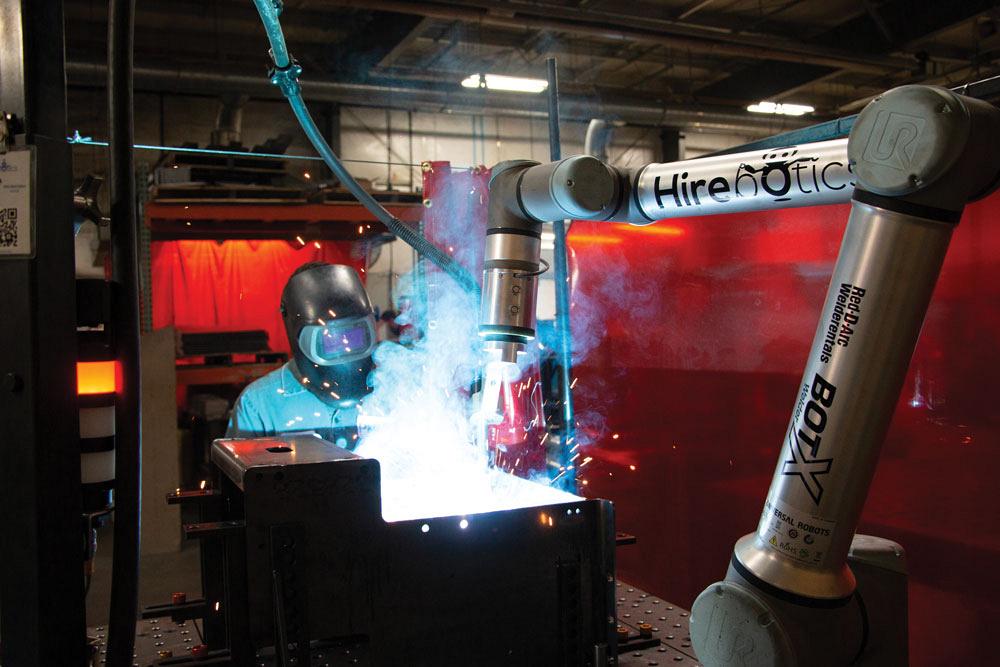

Cobots have become attractive for manufacturers because of their inherent flexibility. For instance, the new for-hire BotX Welder—developed by Hirebotics and using Universal Robots’ UR10e collaborative robot arm—lets manufacturers automate arc welding with no capital investment. It handles even small batch runs that wouldn’t be feasible for traditional automation. Image courtesy of Universal Robots.

Collaborative robots, or cobots, have captured the imagination of a lot of shop owners who previously thought that the footprint requirements, programming tasks, and initial financial outlay of a standard industrial robotic cell would be too costly and time-consuming. The way cobots have been marketed over the past couple years presents them as, in some ways, another multi-use tool for your shop. And given the right applications, this is certainly true.

However, like any other capital equipment in your facility, it’s important that it demonstrate its value via a positive, relatively prompt ROI. It’s useful to consider how best to achieve this by thinking through the following points ahead of your cobot deployment.

Identify the Headaches

The first step is to understand where your most urgent needs are on the shop floor.

“The first thing we do is work with the shop manager or owner to understand what the shop’s pain points are,” said Joe Campbell, senior manager of applications development for Universal Robots. “Are you having trouble meeting customers’ capacity? If you’re a welding shop, you probably can’t find enough skilled welders. Or are you having quality issues that a robotic system might help with? Everybody frames their headaches a different way. Although it would seem obvious that these headaches are top of mind for those investing in new technology, the two don’t always tie together.”

Once the pain points are determined, Campbell talked about finding the “dull, dirty, and dangerous” jobs that might be low-hanging fruit for a robotic system.

“Look for applications where you’re not leveraging your skilled workforce or you’re putting them in harm’s way,” he said. “That might be reflected in staff turnover rates in that area or workers’ compensation claims.”

Keep It Simple

Peter Fitzgerald, general manager at FANUC Canada Ltd., encourages a shop considering any sort of robotic investment to keep the initial projects simple.

“Ultimately, you want a project that has lower technical risk and a decent payback,” he said. “The simpler the project, the easier it is to introduce the technology to your operations and to your staff, and respect that there is going to be a learning curve. Starting with a simple task may not involve a big payback, but it builds a much better foundation for future success.”

An ideal starting project for a cobot in a shop should be a job that is highly repetitive and involves coarse movements. Picking up and putting down boxes, picking and placing parts, and perhaps making a single weld bead on a very simple part are all jobs that don’t require pinpoint precision. Image courtesy of FANUC.

Fitzgerald also noted that you’ll find your in-house champions for the technology this way.

“Those champions will help you find future applications that will fit with your robotic investment,” he said. “Some customers actually invest in the cobot first, knowing that they need to understand the technology, and they build their in-house champions in the lab, testing its capabilities. Whichever your approach, those champions will be a key component.”

When asked to explain what a good starting project might be for a cobot, both Fitzgerald and Campbell said it should be a job that is highly repetitive and involves coarse movements. Picking up boxes and putting them down, picking and placing parts, perhaps doing a single weld bead on a very simple part - these are all jobs that don’t require pinpoint precision.

“Walking the cobot through these types of jobs gives new users a chance to acclimatize to programming it,” said Fitzgerald. “Quality inspection is another very good cobot application, and because there’s a vision system involved, there is another technology your team can get acclimatized to in the process. Where either the cobot is acting as an assistant in some capacity to the operator or there is a very deliberate operator intervention to assist the cobot in what it needs to do, these are always good applications that will teach the new user a lot about the capabilities of the technology.”

Campbell also noted that the job should involve the cobot running six to eight cycles per minute or less, and carrying no more than 36 lbs at a time.

“A cobot is built to work at human speeds, handling payloads that a human could handle,” he said. “Its productivity is based on the fact that, once it starts, it won’t stop for breaks and does the job consistently cycle after cycle. But it needs to be clear that the project in question needs to meet those parameters.”

Show Incremental Gains

Another advantage to starting with a simple, singular job for the cobot is that it can demonstrate how having the cobot do part of a job can offer a payback that would be harder to realize were the whole process automated at once.

“For small businesses that used to think that automation was an all-or-nothing proposition, finding small, very specific jobs that a cobot can do side-by-side with human operators can open their eyes to greater opportunities,” said Campbell. “It’s not necessary to solve the $1 million problem immediately. Start by solving a $75,000 problem.”

With the right simple incremental application, rollout can be rapid also.

Flexibility is the big draw with a cobot, and systems have been developed across the industry that demonstrate this well. The Fab-Pak Cobot robotic welding system shown here can be moved to the part you need to weld, all while safely operating in tandem with your production staff. The idea is to have a tool that serves needs better than a fixed weld cell can. Image courtesy of FANUC.

“We have an integrator that specializes in machine load/unload cobot applications,” said Campbell. “He has what he calls a ‘threeweek/three-day guarantee’ by which he’ll ship a customer a system in three weeks, then he’ll be on-site for three days and the customer will be in full production at that point. Not every application will be that simple, but a very focused approach to a rollout helps to achieve these types of results.”

Be Safe

The flexibility of a cobot, as explained, does have its advantages. The lead-through teach, for instance, can save setup time on low-run or custom weldments (although as Fitzgerald points out, some newer standard industrial robots now can be similarly equipped). What doesn’t change between using a cobot and a regular industrial robot is the need for safety.

“Cobots are now being equipped to weld and prepare metal surfaces for other processes using abrasives,” said Fitzgerald. “In applications like these, there is still a real physical threat to an operator who is close to the cobot. So when considering investing in a cobot, you have to consider the workspace, the access for the operator and others in the shop, physical clearances, and how physical interactions are going to work. A cobot may deploy differently than a standard robot, but it still has to follow those safety rules.”

Is It a Cobot’s Job?

To get the right payback on a job, you have to be sure you’re applying the right tool to that job. Depending on the outcome you’re looking fora cobot might not be the right answer.

Fitzgerald said that there are four different levels of collaboration, supported by different technologies, and a shop needs to consider which level makes sense for their application.

“A safety-rated monitored stop environment, for instance, is one where the robot stops when a person enters the space in which it is operating,” said Fitzgerald. “That’s the simplest level of collaboration. A common use of this type of system is a manual loading station. In this scenario, an operator can manually load a part to the robot’s tool or a manual inspection station. This allows the operator to inspect parts periodically as the robot unloads them from a machine. To achieve these types of applications, light curtains and a safety pressure mat could replace a panel of fencing.

“The second level is hand guidance, which allows robot motion through the direct input of an operator from a hand-operated device,” Fitzgerald continued. “Here the operator can perform lead-through teach, but once the operator is out of the perimeter of the robot, it can speed up to perform tasks faster.

“The third level involves speed and separation monitoring, where scanners around the robot react to what they detect around the robot. The robot will slow down depending on what it detects in its environment.”

Here we see a UR10 cobot being used on a mechanical press. The success of this first installation paved the way for new automation projects with cobots at the company involved.

All three of these versions of collaboration have their ideal applications. Cobots are just the final iteration in that four-tier system.

“It’s important to consider what the application you are looking to automate requires,” said Fitzgerald. “For instance, a standard industrial robot, when you step away from it, can run at 4,000 mm/sec. A cobot, by the nature of its design parameters, is going to run at no more than 1,000 mm/sec. So for many applications where 90 per cent of the time there is no need for operator interaction, speed and productivity are much more important.”

Cobots are a flexible tool that, for the right application, can save shops time and money. Make sure that your plans make the technology stand out as best it can.

Editor Robert Colman can be reached at rcolman@canadianfabweld.com.

FANUC Canada Ltd., www.fanucamerica.com

Universal Robots, universal-robots.com

About the Author

Rob Colman

1154 Warden Avenue

Toronto, M1R 0A1 Canada

905-235-0471

Robert Colman has worked as a writer and editor for more than 25 years, covering the needs of a variety of trades. He has been dedicated to the metalworking industry for the past 13 years, serving as editor for Metalworking Production & Purchasing (MP&P) and, since January 2016, the editor of Canadian Fabricating & Welding. He graduated with a B.A. degree from McGill University and a Master’s degree from UBC.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

Aluminum MIG welding wire upgraded with a proprietary and patented surface treatment technology

Achieving success with mechanized plasma cutting

Hypertherm Associates partners with Rapyuta Robotics

Gema welcomes controller

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI