- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Understanding Carbide

As tungsten carbide prices rise, are manufacturers replacing solid tools?

- By Joe Thompson

- June 15, 2013

- Article

- Management

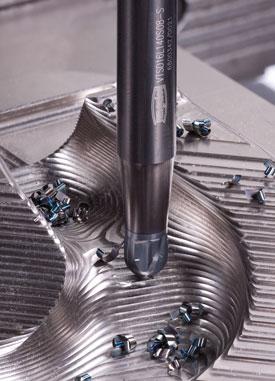

New technology has enabled some cutting tool manufacturers to produce indexable end mills, which essentially are small end mills threaded into a shank. Photo courtesy of Tungaloy America.

Rising commodity prices affect every facet of our lives; you only have to look at the price of incoming raw materials and fuel to see this is the case.

One of the commodities most affecting tooling suppliers, and the products they manufacture, is tungsten carbide. Over the past decade, tungsten carbide prices have risen sharply. In 2004 alone the price rose 500 percent. According to the Tungsten Investing News, however, the price is not only high when compared to a decade ago, it also has a tendency to fluctuate rapidly.

This can make it difficult for suppliers to guarantee prices.

China, which controls nearly all of the global tungsten trade (roughly 80 percent), has been holding a tight rein on its supply recently to keep the price of this rare-earth metal trending upward. These rising tungsten prices have made tool recycling more attractive and, in some cases, changed purchasing patterns.

But has the rising cost of carbide actually affected the use of solid-carbide tooling?

According to Walter USA Product Manager Pat Nehls, productivity, not price, should drive purchasing decisions. New coatings and high-performance tool designs are two examples of productivity-boosting technologies that can have a dramatic effect on performance.

“When the customer shows high performance increases, the cost of the carbide becomes less important,” said Nehls. “Ultimately, we are selling cost per feature. When a more expensive tool produces features at a lower cost, the customer is satisfied.”

Many years ago high-speed steel (HSS) and brazed-carbide cutting tools were very popular. Today fewer and fewer shops make use of them, with solid-carbide and indexable tooling being the norm. One of the reasons for their waning use is that when a tool is at the end of its life-span, it is taken out of the machine and reground.

Reground tools have a shorter life, and predictability becomes much more difficult. A tooling “float” also must be created to ensure that tools are on hand when needed.

The use of indexable inserts, in particular, has eliminated the need for this procedure.

Cost per feature is normally lower with indexable inserts because they have two or more usable cutting edges. Photo courtesy of Walter USA.

While indexable inserts are certainly the tools of choice in many applications, shops aren’t necessarily choosing them over solid-carbide tools.

“Each tool type has its own features and benefits,” said Nehls. “For example, solid drills will typically produce holes to tighter tolerances, perhaps eliminating the need for secondary operations. This makes the solid tool the more economical choice anyway.”

Solid drills also are available in smaller increments between sizes.

On the other hand, Nehls said that indexable drills have a tighter diameter tolerance band because of their assembled nature. Cycle time may be increased, but the cost per hole is generally lower. Ultimately, the requirements of each project guide tool choice.

Conserving Carbide

“Today when an insert becomes dull, we simply index the insert and can expect relatively good repeatability and consistency,” explained John Mitchell, general manager of Tungaloy America. “Insert pressing and coating technologies advanced to where there are now major improvements in performance and chip formation. Few machine shops would want to go back to the days of HSS and brazed cutting tools. However, many shops continue to use solid-carbide tools.”

The premise is the same: Use the tools, take them out of the machine, regrind them, reset the tool, and adjust the offsets. A reground solid-carbide tool will last 80 percent as long as a new tool. In most solid-carbide end mill applications, for example, the end mill takes a conservative depth of cut (0.100 in.), yet the tool may be 3, 4, or more inches long.

“That’s a lot of carbide … nearly the entire end mill is made of carbide. This is inefficient given the rising cost of carbide and the fact that only 3 or 4 percent of this tool is actually in cut,” said Mitchell. “The same evolution that happened with HSS and brazed tools is occurring rapidly now.”

New technology has enabled some cutting tool manufacturers to produce indexable end mills, which essentially are small end mills threaded into a shank.

“Obviously, since the indexable carbide portion is only a fraction of the size of a solid-carbide tool, the cost to produce this indexable end mill can be much lower,” explained Mitchell. “The true benefits of this technology are not in the cost, but rather in its performance.”

Because the end mill is screwed into a shank, the shank can be made of different materials to produce different results. For example, for a roughing operation, it is best to use a steel or other heavy metal shank.

According to Mitchell, these shanks offer a dampening effect, which improves roughing performance by enabling a heavier cut to be made. When finishing or an extended reach is needed, it is best to use a carbide shank.

Reducing Setup Time

“Solid-carbide end mills perform at their best when held in a shrink-fit holder, but removing a used solid-carbide tool from a shrink-fit adapter can be cumbersome and time-consuming,” said Mitchell. “An indexable end mill is simple to index; in fact, most indexes can be performed right on the machine in seconds.”

After indexing the tool, an offset is not always required because the repeatability of these tools is very accurate. Setups are easier with this type of tool as well, because the location of the tool is predictable.

Even when a collet is used, the tool changes are time-consuming and labor-intensive.

First, the end mill needs to be removed, reground, and placed back into the collet holder. Then the tool must be set up using a height gauge or tool presetter, before being placed back in the machine. Following this, a trial cut is typically performed and offsets calculated and entered into the control, before the tool can run.

An indexable end mill can be switched out directly on the machine.

Recycling Carbide

The days of throwing worn tools away are over. Because only a small amount of the carbide is actually worn away during machining, inserts and solid tools should be kept as scrap and recycled.

And, in an effort to control production costs, many tooling manufacturers now offer carbide recycling programs to reduce their dependence on new carbide purchases.

“Over the last 20 years, we have seen a significant increase in recycling all scrap materials, including carbide,” said Nehls. “Customers are savvier with respect to their total production environment, and there is a lot of money in used carbide.”

Solid or Indexable

According to Pat Nehls, product manager for Walter USA, solid tools produce more precise features, which makes them the preferred tool when finishes matter.

“Solid drills have diameters ground to very tight tolerances,” explained Nehls. “When the drilled hole must be precise without additional finishing operations, the solid drill may be the best choice.”

Indexable tools, on the other hand, have greater diameter tolerances due to the tolerance of the basic body as well as the tolerance of the insert used. For this reason, indexable drills are normally considered roughing tools.

Some operations may require solid tools when the hole diameter is less than the size range of indexable tools.

Which tooling type is used also affects setup time and production.

Initial setup time is increased with indexable tools because the inserts must be loaded into the tool body. Subsequent tool changes can be more economical in terms of time, though, because resetting the tool length is not necessary when indexing the inserts.

That is not the case with a solid-carbide tool.

“Reconditioned solid drills and mills must be reset after reconditioning due to the changed overall length and diameter,” said Nehls.

During production, indexable tools typically run at lower inches per minute (longer cycle time) than solid-carbide tools because they use a lower feed per revolution. However, the cost per feature will normally be lower because inserts have two or more usable cutting edge

“There is a balancing act between cycle time and cost per feature,” said Nehls.

Related Companies

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI