- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Try a Close Shave

Straight walls, formability, and reduced sheet deformation will follow

- September 11, 2014

- Article

- Fabricating

Punching a hole isn’t a straightforward proposition. About the first third of the hole wall’s depth is straight and conforms to the punch size. Then the material breaks away into a bell shape. The bottom of the hole is wider than the top. This inconsistent dimension can cause problems for some applications.

The punching action also affects the material. The cold-forming process modifies the grain of the material along the sides of the hole, increasing its hardness and reducing its formability. This can present problems for some secondary operations.

A two-step shaving operation can produce a punched hole with parallel walls and return the material to a state close to its original characteristics.

Scott Tacheny, special applications engineer for the Punching Division of Wilson Tool International, White Bear Lake, Minn., talked with CIM-Canadian Industrial Machinery about the advantages of a shaving operation.

CIM: Why use a shaving process?

Tacheny: A lot of times people need a straighter surface inside a punched hole than what they get with a punching operation. They may be using the hole as a bearing surface that needs a straight wall, or maybe they need to add a certain number of taps that couldn’t be achieved because of the natural breakaway of a punched hole.

CIM: How does shaving produce straight holes?

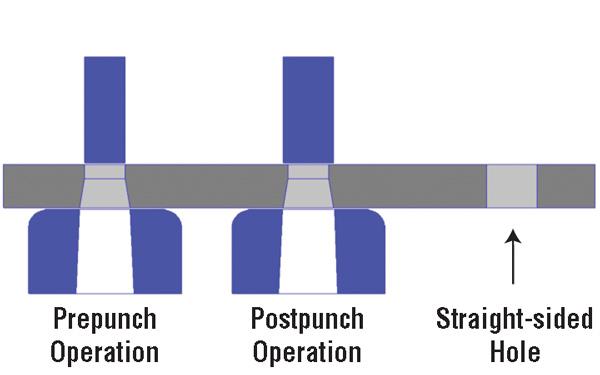

Tacheny: Shaving is a two-step process. The prepunch operation creates a hole with the initial piercing action; the postpunch follows to shear off an additional thin section of the material to create the straight walls. Shaving off the smaller amount of metal doesn’t strain the material to the breaking point like the initial punch does, so you don’t get the deformation. The second hit creates the straight walls.

CIM: How does it affect the metal?

Tacheny: The first punching process cold-works the initial pierce, which changes the material’s formability. During the second shaving operation, which is more of a cutting process, material reaction is similar to what you get during a machining operation. The metallurgy of the shaved wall is more like the original material and will work better when it goes into an extrusion.

A two-punch shaving operation can eliminate the breakaway configuration and provide parallel sides within a punched hole. Illustration courtesy of Wilson Tool International.

CIM: Does edge quality change?

Tacheny: At times engineering drawings will call for a sharper edge on a hole than what can be achieved with a punch because of the rollover. Shaving helps here too. It removes a lot of the rollover, leaving a sharper edge. A sharp edge might be specified when making a stairstep, a tread plate, or when the next process is a form-up that can’t be completed with rolled edges.

CIM: How does shaving add to productivity?

Tacheny: When somebody wants a hole with straight walls, they will frequently move the sheet to a machine center and drill the hole, so they are adding a secondary operation at a second workstation. Keeping the process on one machine saves costs, time, and maybe even fixturing.

CIM: How do you determine the proper tool size and clearances for a shaving process?

Tacheny: Start with the finished hole size and look at the process in a backward direction. You are going to have two punches and two dies. Both dies will be punch No. 2 plus 1 to 11⁄2 percent of the material thickness for the clearance—a pretty close clearance. Punch No. 2, the one that does the shaving, is going to be the desired hole size. For the shaving process, you want to remove a minimal amount of material. If too much is left to shave off, you are just cold-working the material again. Punch No. 1 is die size, the same size die as that used with the shaving punch, minus 10 to 20 percent clearance.

One of the things about this process that sneaks up on people is that the finished hole is usually smaller than the punches. The material is going to expand a bit due to its elastic recovery. The hole can also be 0.0005 in. smaller than the shaving punch, so that should be taken into account when determining punch size.

CIM: Are there special tooling considerations?

Tacheny: When you are removing such a small amount of material, you have to be concerned with pulling the slug back up. We suggest some sort of pocket or concave shape for a shaving punch to make sure it moves in the direction of the slug.

It’s not a bad idea to have a guided stripper plate to maintain a nice, tight clearance between the punch and the stripper plate and not just the punch and die. That helps keep the punch moving straight so it won’t kick off to the side.

CIM: Are any precautions necessary while using a shaving process?

Tacheny: Heat generation is probably the biggest problem. Some people equate shaved walls to a burnished edge, so you may want to use lubrication or a special coating on the punch so it doesn’t gall up. A shaving operation can cause galling significantly faster than punching.

CIM: Are there any unexpected benefits to the process?

Tacheny: A surprising result of shaving is reduced sheet distortion. Manufacturers who deal with a lot of patterns or do a lot of perforating can end up with a fair amount of sheet distortion. One equipment manufacturer ran its own tests that showed a 50 percent decrease in sheet deformation for a shaving or postpunching process when compared with a punching process. The reduction is attributed to the removal of the cold-worked area that is in tension. By removing it, the material relaxes a bit.

Shaving Is Equipment-Friendly

On the equipment side there are very few restrictions when it comes to implementing a shaving process. Whether you are using a high-end machine or a single-station punch, the main consideration is ensuring that the equipment is properly rated for the material thickness.

Dan Caprio, punching products sales manager for LVD/Strippit, Akron, N.Y., answered shaving questions from the OEM perspective.

CIM: Does tonnage come into play?

Caprio: Normally the thicker the material, the more the breakaway comes into play. Breakaway can happen with thinner stock, too, but typically the configuration of the hole walls comprises such a small area that it isn’t a concern. As long as the tonnage of the machine is properly rated for the material thickness, the shaving process is not a problem.

If you can create the prepunch hole, you will be able to straighten the hole walls with a shaving operation. The shaving itself requires less tonnage because it removes a small amount of material.

CIM: Is punching speed a factor?

Caprio: No, especially on the prepunch. If you are doing a steady flow of 1⁄4-in. punching over an entire sheet, you may want to slow the process down or even change punches so you don’t build up heat. We recommend that customers doing a lot of punching consider a coating on the punches. Coatings can pay off whenever you put heat into the part. But that isn’t necessary for the secondary shaving process.

CIM: What are the equipment limitations?

Caprio: Following the prepunched hole, a 0.002-in. clearance would be needed for the postpunch shaving operation. For that reason I would recommend using a fixed station to perform a shaving operation.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI