- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

The Advancement of CNC

To keep pace with machine tool advances, the new generation CNCs must be easy to use, while at the same time offer the functions necessary for today’s manufacturers

- June 29, 2010

- Article

- Automation and Software

As five-axis machining becomes more popular, the demand for advanced control functions related to five-axis movement has increased.

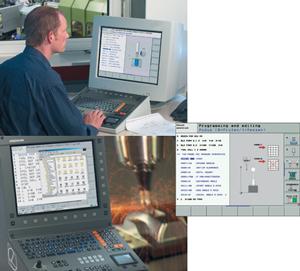

New CNCs must not only keep up with advances in machine tool technology, but also the needs of manufacturing facilities in terms of programming and machine operation. Complex machine movements, especially in true five-axis machining, are driving the need for many new CNC functions.

However, it is the end user that must be able to put these new functions into practice.

“As demand for true five-axis machining increases, the demand for more advanced functions related to five-axis movement has also increased,” explained Heidenhain Canadian Regional Manager Scott Warner.

CNCs must also be easy to understand and to use. This reduces programming time that increases operation speed and therefore productivity, which in today’s competitive market is extremely important.

“I think the expectations of the end user have changed. Customers are being exposed to more advanced, intuitive electronics and software in such devices as the BlackBerry® and Apple iPod®. This has increased the realization that other items, such as their CNC, can also be more intuitive,” said Warner. “Shop owners are able to get more from varying operators in a shorter period of time, spend less time training, and therefore get more time machining.”

Advanced Features

Due to the complex machine motions created during multiaxis machining, and because of steadily increasing rapid traverse and machining speeds, it is increasingly difficult for the machine operator to foresee axis movements inside the machining envelope. This has created a need for collision prevention technology.

In Heidenhain’s new iTNC 530 CNC, for example, integrated dynamic collision monitoring prevents collisions between the tool and machine components and also between the tool and fixtures. This is possible in both the Program Run mode and also the Setup mode when the machine axes are moved manually by the operator.

The CNC detects when the tool is in danger of causing a collision and stops the axis movements before this can happen, while at the same time issuing an error message.

Thermal instability inside a machine also can cause quality issues to arise in multiaxis machining. These thermal influences affect machine accuracies and therefore part accuracies.

These inaccuracies can be reduced by kinematic compensation protocols in the control. This new feature uses a 3-D touch trigger probe to measure the position of a known and exactly dimensioned calibration sphere from various rotated axis positions.

CNC systems today have the ability to offer both conversational and G-code programming options, a flexibility necessary for today's manufacturing environment.

The operator then receives a log that shows the true accuracy during tilting in real time. If desired, this feature, called KinematicsOpt in Heidenhain’s system, can automatically optimize the axes that have been measured.

As the trend moves toward higher feed rates and more accurate cutting paths, CNCs keep pace through shorter block processing that comes only through better joint engineering relationships between the control builder and machine builder. In addition, advanced contour filters, new algorithms, and the latest in computer hardware reduce machining time and errors.

“We have increased the memory on the control itself to allow faster acquisition of data, even faster than the current Ethernet interface,” said Warner.

Data Processing

There are two options for entering data into a control. The first entails entering data directly at the control; the second, in an offline session.

“As customers do more powerful programs at the control, the graphical interface allows the operator to check his work, reducing programming errors,” said Warner.

Performing G-code programming and editing tasks directly at the control is a process that some shops find practical, and others do not. However, according to Warner, its total elimination is impractical.

“For simple programs [this elimination] would be a mistake,” said Warner. “For more advanced programs, editing should be done back at CAD phase, where the program was originally produced.”

In cases when editing must be done at the control, CNC builders have given the user the ability to transfer programs into more intuitive, conversational programs to allow easier editing.

CNC systems today have the ability to offer both conversational and G-code programming options, a flexibility necessary for today’s manufacturing environment.

“Everyone is realizing that the more capable a system is, the more you can produce with it,” explained Fagor Automation Sales Manager Wayne Nelson. “You can’t just have a conversational CNC or a G-code system. You need to be able to feed data in both ways. Even down to individual operations, you must be able to use the strengths and insights of every employee to make deadlines that help the bottom line.”

Previously lot size determined the type of data input. Small lots were done at the machine, and large projects were created elsewhere. This is no longer the case.

“Everyone in the operation must be able to use the system to their best abilities so you can focus on productivity with the least amount of interference,” said Nelson. “If a machinist can understand the full depth of capability of the system, that’s great, but it is more usual that the operator will be limited in his time to learn the system.”

This creates a need for a single control that allows a simple approach initially, but also will allow more advanced features when the time is correct. The system must be easy to use, without giving up the strengths of full-blown CNC.

While old habits die hard, editing G-code at the control should be eliminated when possible, added Nelson.

“G-code will always have a home. In five-plus-axis machining, trying to produce a [program in a] CNC conversational system would be mind-boggling. Also, never forget that the best conversational operations are always relating internally to G-codes,” he added.

With a Fagor CNC users can teach-in numerical values, write-in values, and also calculate the values while drawing the part both conversationally and in the Editing Assistance mode. All three types of input are needed for the CNC to be as productive as possible.

Also, the operator should be able to quickly and easily use one screen to make all changes to an operation. The company’s 8055MC and TC controls, as well as the new 8065 series of controls, allow this.

“You can’t be bouncing to three different screens to make one functional change in an operation,” said Nelson.

CNC Graphics In Conversational Operations

Human-machine interface (HMI) graphics shown during conversational operations and path/solid graphics for program testing are both critical in today’s machining.

Icon-driven, conversational programming CNCs have graphic depictions of the cycles that let operators easily identify and choose the operation that is needed. As mentioned, a single page should have all the pertinent information about the operation, including roughing, finishing, machining conditions, spindle specifications, choices of conventional or climb milling, ramping angle between layers of machining, and cycle options.

“From that graphic representation of the operation, each individual requirement is defined both in the graphic and a supporting text line that help the operator understand exactly what is needed,” explained Nelson.

Each operation can be run individually or as part of a saved program, and it can also be changed at a later date.

The other reason for a graphical interface is for path/solid graphics.

“Ever crash a high-speed machining center?” asked Nelson. “Let’s do it on the screen.”

In the current Fagor 8055 and 8065 series, for example, feature graphics plots and representations of a part program run in solid 3-D graphics on mills and 2-D graphics on lathes. The lathe units also show a proportional view of the tool and nose radius relative to the part.

Milling path graphics and solids also give the operator controlled choice of simultaneous screens in each plane and isometric.

“We as developers must always find ways with which we can more easily relate between the operator and his task,” said Nelson. “A mountain of work already has been done to make HMI more modular for the integrator and simpler for the operator, especially in multiple-channel systems. Features like premade five-axis graphics, G-codes, and crash zone relationships between channels and axes must keep stride with speed and diversity of the control. It also has to be understandable so it can be functional and safe to operate.”

For more information, visit www.heidenhain.com and www.fagorautomation.com.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI